In honor of NF2 Awareness Day (May 22), the Children’s Tumor Foundation released a brand new resource, Understanding NF2, an eight-page educational comic book that tells the true story of Billy Nguyen, an NF2 patient and a member of CTF’s Junior Board. Here is Billy’s story, in his own words, and the journey upon which the comic book is based. You can also watch this video featuring Billy.

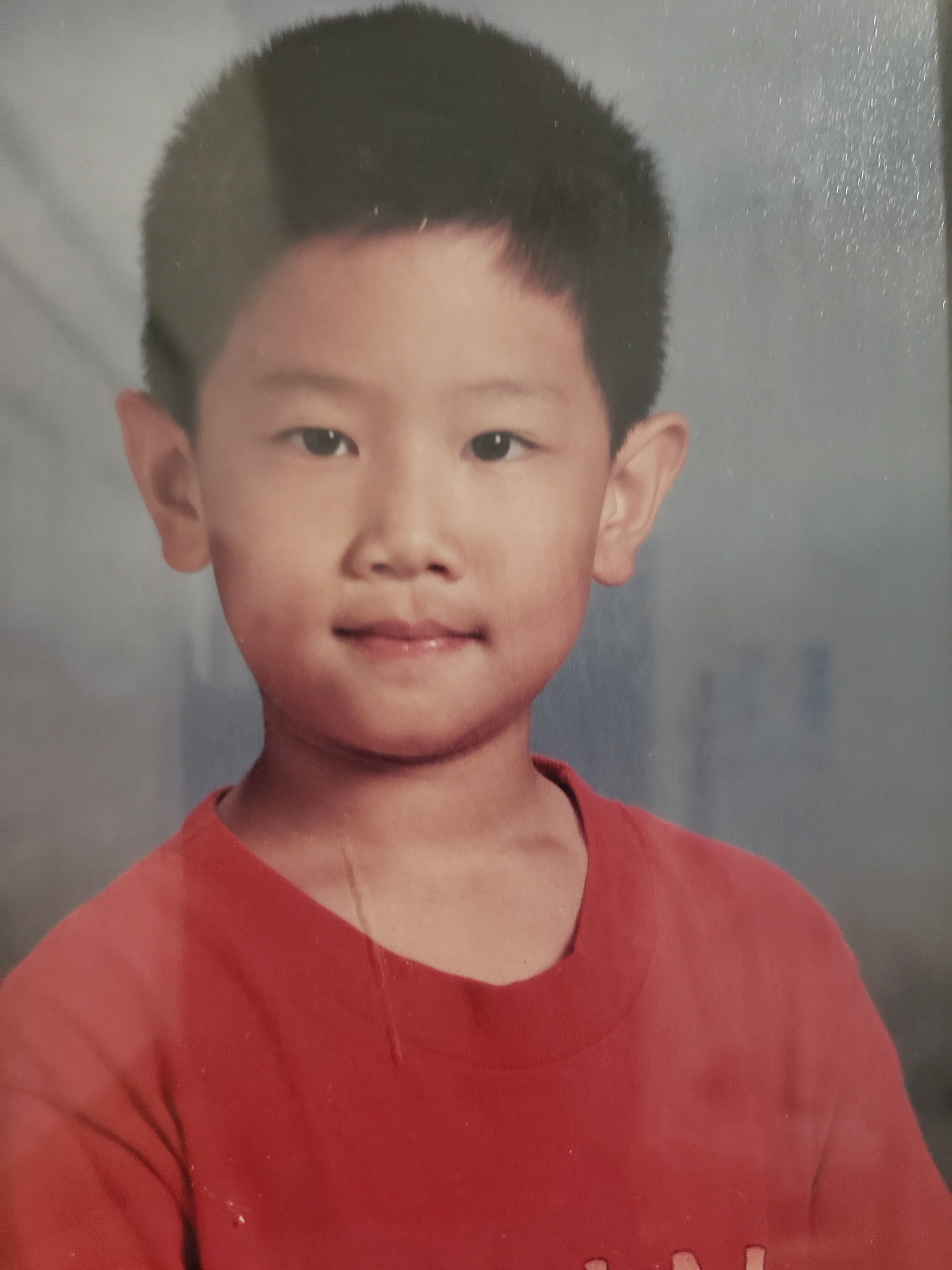

My name is Billy, and I am currently a pediatric resident physician at the University of California, San Francisco. I’m a first-generation immigrant – I was one year old when my family immigrated to the United States from Vietnam.

My story with NF2 begins at age six. I was first diagnosed after a visit to the optometrist, who detected abnormal cupping of the optic nerve. My parents took me to several doctors and after a year of referrals, doctors’ visits, and an MRI scan, they found a meningioma on my optic nerve, and hallmark bilateral vestibular schwannomas. Together, all highly characteristic of NF2.

So, the diagnosis was made shortly afterwards, at age 7. I think most kids who are diagnosed with any “chronic” disease at such a young age don’t really understand what it means, and I was one of them. I didn’t start to understand the significance until I was 13, when I was told that one of my meningioma had rapidly progressed. My neurosurgeon said to me, “Looking at the tumor’s progression rate, if you don’t get this surgery, you’re probably going to lose your vision.”

So, the diagnosis was made shortly afterwards, at age 7. I think most kids who are diagnosed with any “chronic” disease at such a young age don’t really understand what it means, and I was one of them. I didn’t start to understand the significance until I was 13, when I was told that one of my meningioma had rapidly progressed. My neurosurgeon said to me, “Looking at the tumor’s progression rate, if you don’t get this surgery, you’re probably going to lose your vision.”

My parents are well-educated, but English isn’t their first language and medical terminology is difficult for them. My parents were deferring to me, asking, “Can you translate what the doctors are saying?” It was really hard. I was a 13-year-old freshman in high school, having to figure it out for myself, asking; “What do I have? What do I do? I have a brain tumor, but is surgery the right option?”

For children from immigrant families, a scary and confusing situation can become more incredibly difficult when the child has to translate obtuse medical terms for their parents. Often they themselves can barely understand what’s going on, or process what’s going on. It’s a monumental ask for a child.

I ended up getting surgery during Christmas of freshman high school year, six months after that clinic visit. I spent the holiday in the hospital, which was not the best, but at the same time it was a bonding experience. My mom stayed with me for that entire week and really helped me through the process. My mom was my rock, sitting or sleeping by my gurney or feeding me the  occasional ice chip. My father and siblings came by every day. It was great. I mean, there were hard moments, like the nausea, vomiting, and searing pain over the craniotomy site. But we also shared some really great memories. I remember nurses dressed as Santas coming around the unit, dropping off large neatly wrapped presents – that was phenomenal.

occasional ice chip. My father and siblings came by every day. It was great. I mean, there were hard moments, like the nausea, vomiting, and searing pain over the craniotomy site. But we also shared some really great memories. I remember nurses dressed as Santas coming around the unit, dropping off large neatly wrapped presents – that was phenomenal.

The hardest part after surgery is recovery. I had to relearn how to do everything. Patients who have undergone a brain surgery don’t really tell you, “Oh, I had to learn how to use the restroom again, I had to learn how to walk again, and write again.” The things that we’ve taken so much for granted, now post-operatively, you have to completely relearn.

After the break, I went back to school as a high school freshman with this giant scar and staples on my forehead. That was not a pretty sight.

Fast forward ahead, I graduated from high school at the top of my class and ended up going to the University of California, San Diego, staying in my hometown. I decided to study neuroscience and physiology. I started working in Dr. Clark Chen’s lab, where I worked on glioblastoma, which is stage IV brain cancer and the most common and lethal primary brain cancer in adults. I was looking at the underlying mechanisms by which glioblastoma becomes resistant to both chemotherapy and radiation and ultimately searching for biochemical targets to increase survival.

It was around this time that I realized I wanted to become a physician. I’m sure part of the decision was the connection I felt as a patient living with NF2. But I’d be remiss if I didn’t give credit to my own wonderful physicians. I was really influenced by my pediatric neuro-oncologist, Dr. John Crawford from Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego. He had cultivated in me a love for medicine and a true desire to help patients. He was incredibly nurturing and saw me more than a patient, encouraging me to join the healing arts.

Towards the end of my time at UCSD, I graduated Magna Cum Laude in neuroscience and physiology, and found out I was accepted to UCLA for medical school – and not only accepted, but also offered a full ride. It was absolutely amazing!! During my white coat ceremony, I texted Dr. Crawford a photo of me in my white coat and wrote, “Hey Dr. C, just wanted to say hi. Love you a lot and am in this white coat because of you. Much love, Billy.” I owe a lot of my career path to him. We’re very close and we still keep in touch.

Jumping back to college, I felt as if I was living between MRI scans. I was going to a lot of appointments, going to MRI, to audiology, to neuro-ophthalmologist, and hoping nothing had happened. In the midst of all the celebration with getting accepted into medical school, about a month before graduation, I found out one of my tumors had tripled in size. It was a real blow. I was struck by how vulnerable I was, to be at the top of my game, doing so well, with a full ride to this very prestigious medical school…and then this happened.

Jumping back to college, I felt as if I was living between MRI scans. I was going to a lot of appointments, going to MRI, to audiology, to neuro-ophthalmologist, and hoping nothing had happened. In the midst of all the celebration with getting accepted into medical school, about a month before graduation, I found out one of my tumors had tripled in size. It was a real blow. I was struck by how vulnerable I was, to be at the top of my game, doing so well, with a full ride to this very prestigious medical school…and then this happened.

I found myself at a crossroad in my life. I thought, “If I can’t take care of myself, how can I take care of my patients?” It was a difficult point in my life, and I really doubted myself and wondered whether I should go into medicine.

Ultimately, I decided to go to continue with medical school, in part because of the safety net of having ‘nothing to lose,’ no financial burden if it doesn’t end well. Three months into my first year at UCLA medical school, on a follow-up MRI, I found that the meningioma had doubled again. That was a nine-fold increase from where it had been just a few months before.

My neuro-oncologist at UCLA, Dr. Leia Nghiemphu, started me on a clinical trial, but the trial didn’t work for me. I was having all these horrible side effects, lost 20 to 30 pounds, and worst of all, I began losing my hearing on the left side. My audiogram went from 100% serviceable hearing down to 40%.

I think that was the lowest point in life. Medical school is already really freaking hard, and now it’s near impossible without my hearing. I almost dropped out. I don’t think there’s any way I could finish medical school if I was going deaf.

Fortunately, we switched to a different therapy regimen, starting Bevacizumab, which changed everything. Six months to a year later, I was back to my baseline normal hearing, and I was able to start my third year, our clinical year.

It was during this year when I finalized my decision to go into pediatric neuro-oncology. I realized that I love having a long-term connection with patients, and that perhaps I can inspire young patients who, like myself, can’t see what their life can be like after brain surgery. I never thought I could be a doctor. I thought, maybe a math teacher, businessman or maybe a lawyer. Becoming a physician seemed too far out of reach.

One experience that influenced my decision was with a seven-year-old patient who had osteosarcoma, which is a very aggressive bone cancer, in his leg. He had undergone an above the knee amputated and was here for chemotherapy. His mom and I were talking, and in conversation I told her in passing, I had brain surgery when I was a kid. Her face lit up and she smiled. “But you’re a doctor now and Johnny can be a doctor. See Johnny, you can do it too. No excuses now. This cancer doesn’t mean you can’t do anything you want.”

Interactions like that really made me think about my own experience as a patient. My NF2 can help me be a better doctor, and shape how I relate to patients. The perspective I bring is, “Well I’ve been in your shoes and I know how much this sucks. I know how much pain, fear and confusion there is. I did it, and now we can too. I’m sorry I can’t make it all go away. I’m not sure who can. But I can join you on your journey if you’ll have me.”

I remember another clinical experience with a four-year-old patient, who had recurrent Wilms tumor in the kidney. Her family was in the inpatient room, while she was playing with princess dolls in the gurney. Her mom was the first to speak. She asked very good questions, like: “How long will chemo be? How hard will this be on her body? What will the recovery be like?” Then her mom asked the team a question that still haunts me; she asked, “Do you think it’s worth it?”

This made me think about the first time any patient undergoes treatment, whether it be chemo or surgery or radiation. Everyone is so optimistic. Everyone’s very, “We’ll get through this! We’ll fight this to the end.” Even our words, “war on cancer…beat cancer,” speaks to how ready we are to fight; optimistic that this is a fight we can and will win. But then the second and third and fourth time around, now the entire family, the medical team, the patient knows what’s ahead: how excruciating the surgery is, how incredibly slow the recovery is, how much life we drain with infusions of chemotherapy, of toxins. And at what cost?

This made me think about the first time any patient undergoes treatment, whether it be chemo or surgery or radiation. Everyone is so optimistic. Everyone’s very, “We’ll get through this! We’ll fight this to the end.” Even our words, “war on cancer…beat cancer,” speaks to how ready we are to fight; optimistic that this is a fight we can and will win. But then the second and third and fourth time around, now the entire family, the medical team, the patient knows what’s ahead: how excruciating the surgery is, how incredibly slow the recovery is, how much life we drain with infusions of chemotherapy, of toxins. And at what cost?

Is it worth it? That’s a hard question to answer. She’s four, and this treatment might work. It might not. It’s all so unclear. But that is a decision where, I know, I can really help my patients navigate. Just like how I helped navigate the decision to my parents as the naïve and confused 13-year-old boy. Hopefully wiser. Hopefully more experienced. It’s an experience we can get through together.

Right now, at age 25, my hearing is stable, but I’m under no illusion that things will stay this way forever. For the next ten years, my dream is to pursue an academic career in pediatric neuro-oncology and ultimately spearhead new treatments through basic science. I realize how limited time is. Our current drugs are used just to buy more time until the next big thing. Hopefully we can buy enough time, until we find a more permanent therapy, one that will cure NF2. But until then, we’re in crunch mode.

A wise mentor (Dr. Ted Moore) once told me, life is 10% what happens to you and 90% of how you respond to it. I want to respond loudly and clearly. This disease will not limit me but rather mold me into the physician of my dreams for patients just like me.

You can also watch this video featuring Billy.